Outcome for children in the UK after high-risk neuroblastoma treatment

The UK clinical community has recently released a statement regarding outcomes for children treated on the SIOPEN high-risk neuroblastoma protocol, which includes children in the UK.

You can read their statement here.

The background for this is the increasing numbers of families seeking to access clinical trials not available on the NHS in the hope of reducing their child’s chance of relapse. In particular, there has been unprecedented interest in the Bivalent Vaccine trial at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

One of the biggest uncertainties families have when they are facing the dilemma of whether to try and fundraise to access the Bivalent Vaccine trial or indeed DFMO, thereby extending treatment by a further one or two years, is not knowing what the chance of relapse is for their child if they instead stop and do nothing at the end of treatment in the UK. This situation has been made worse because in the absence of any authoritative information, a number of different estimates have been quoted online and unwittingly picked up and repeated elsewhere by other parents and families.

For some time, we have been asking for more accurate estimates to be provided to fill this void. The problem has always been that to do any relevant post-hoc analysis would involve not using clinical trial data for its intended purposes, thus undermining its scientific credibility.

There has never been any actual research study conducted by SIOPEN that follows specific groups of children e.g. those who are in Complete Remission (CR) with No Evidence of Disease (NED) after having completed all stages of treatment. Event-Free Survival (EFS) and Overall Survival (OS) are recorded from the time treatment for children with newly diagnosed high-neuroblastoma started. They are also recorded as outcome measures for each separate treatment arm from the start of each particular SIOPEN trial.

As part of the most recent SIOPEN Phase 3 study for children with newly diagnosed high-risk neuroblastoma (HR-NBL1) there were a number of separate randomised trials, usually simply referred to by researchers as ‘randomisations’. One of these randomisations was to incorporate the anti-GD2 antibody dinutuximab beta (ch14.18/CHO) with or without Interleukin-2 (IL-2) into the maintenance phase of therapy alongside 13-cis-retinoic acid (isotretinoin).

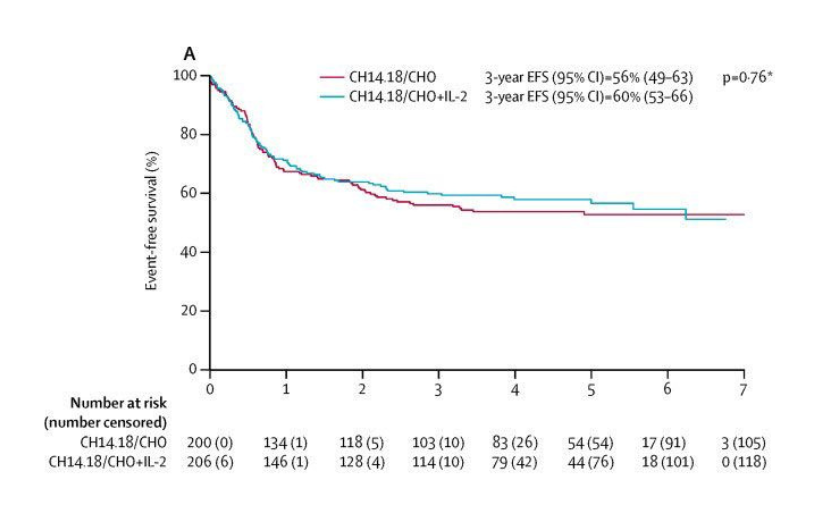

Results of the anti-GD2 immunotherapy randomisation were published in Lancet Oncology in 2018. 3-year event-free survival was 56% with dinutuximab beta and 60% with dinutuximab beta and IL-2. The difference was not statistically significant and so standard of care was determined to be dinutuximab beta alone, as IL-2 caused greater toxicity for no proven benefit. The event-free survival graphs for the two arms are shown in the figure below.

Unfortunately, this doesn’t provide us with the information we are seeking for a number of reasons. Firstly, the starting point is at the beginning of immunotherapy and what we want to know is what happens to those children who successfully complete immunotherapy and still have no evidence of disease. Secondly, these graphs include all children who were eligible to receive immunotherapy – some of whom would not be able to receive either Bivalent Vaccine or DFMO because of the strict entry requirements for those trials. For instance, only children who have no evidence of disease after stem cell transplant i.e. prior to starting immunotherapy and still have no evidence of disease after completing immunotherapy are able to enrol on the Bivalent Vaccine trial.

Therefore, in order to get an estimate of the outcome for children who successfully complete all stages of treatment in the UK and could go on to receive Bivalent Vaccine but for whom treatment instead stops at that point, the data used to construct the graphs above needs to be adjusted as follows:

- All children who did not have no evidence of disease at the start of immunotherapy must be taken out.

- The starting point must be ‘shifted’ forward by 6 months so that it now corresponds with the end of immunotherapy. Any children who relapsed before this new starting point must be taken out.

- All remaining children must be analysed from the new starting point to see what proportion of them relapsed over time.

As the UK clinician statement itself says, 4 out of 5 children remain alive and free of disease 5 years after finishing immunotherapy. So now whenever anybody talks about going for the Bivalent Vaccine trial in the hope that it will reduce the chance of relapse, we know that the best estimate we have puts that chance of relapse at 20% within the next 5 years.

A few things to remember, these statistics only apply to those children who have no evidence of disease both before, and after completing, immunotherapy. They are the group of children who have the best chance of remaining free of disease regardless of whether their parents pursue additional treatments elsewhere. To date, none of the clinical trials that are available after standard UK frontline treatment has finished have shown any proven effectiveness in preventing relapse, despite what might be said or written elsewhere. Finally, what we’re dealing with are just statistics and it’s important to always keep at the forefront of our minds that every child with this disease is a unique individual who will ultimately follow his or her own path.